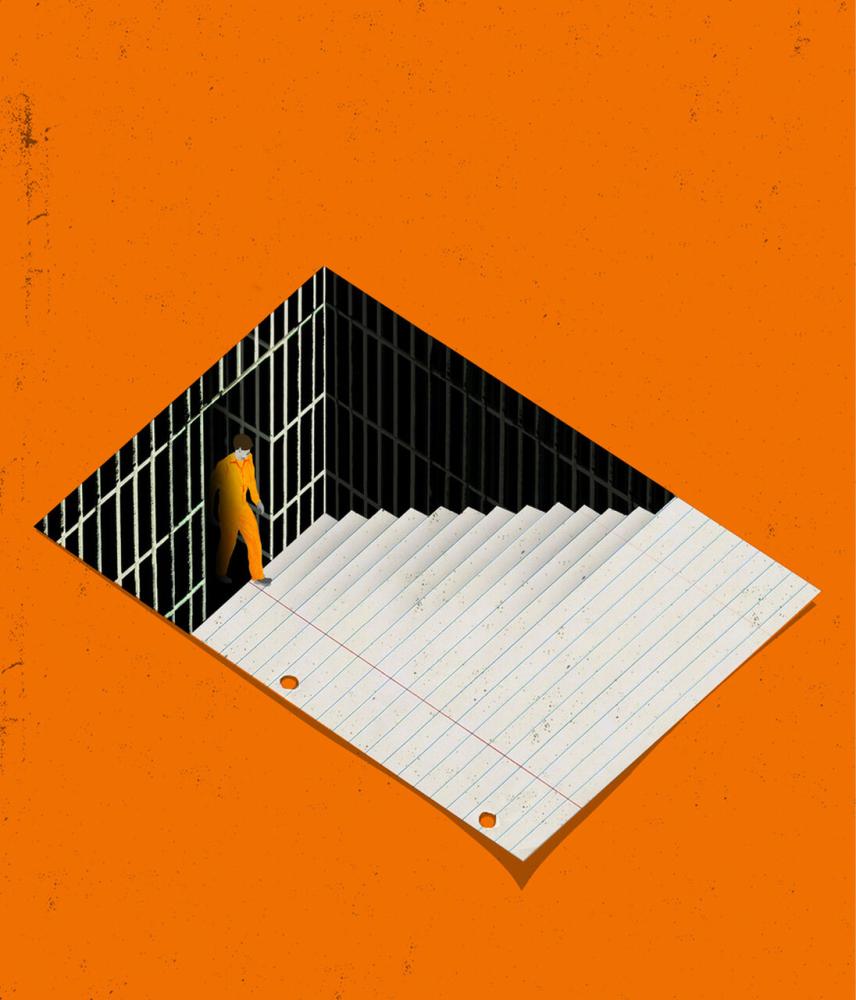

From Sea to Prison: Truly Blind Justice

2nd quarterly report 2023, From Sea to Prison Project

“They framed me for a crime I didn’t commit, I was the victim in a nightmare journey, that’s what drives me mad… How did Italian justice get like this, justice that is truly blind?” H., detained since 2020.

Among the many people who write to us from prison, H. isn’t the only one who tells us that he’s lived through a nightmare, or who asks us what happened to Italy’s sense of justice. They’re the same words people use when they get out of prison as well, and have the chance to tell us their stories face to face. Over the last three months we’ve had the privilege of meeting a range of people who have regained their freedom, and have heard news of releases in different parts of Italy, whether Perugia, Carrara, Bari or Agrigento. Some of these people simply completed their prison sentences, while others have been found innocent thanks to the work of lawyers with whom we have also had the pleasure of collaborating. But there are still many, far too many people behind bars. Over the last few months, we’ve tried to shed light on the people whose imprisonment unfortunately continues. In the first place, we collaborated with the journalist Luca Rondi of Altreconomia on an investigation showing that around 1,100 people are detained in Italian prisons for the crime of “facilitating illegal immigration”, almost all of whom are foreign citizens (1,012). Today we are closely following the cases of 60 such people, accused of driving a boat that crossed Italian borders. More than half of the people we exchange letters with are imprisoned in Sicily, while the remained are in prisons across the country, from Liguria and Tuscany to Puglia and Calabria.

Secondly, in an in-depth article we contributed to the annual report published by Antigone, we analyze how imprisoned captains are among the detainees most effected by racist policies during their detention. Through an examination of some of their stories, we try to demonstrate the deeply repressive nature of the sentences they face, linking this to the politicized character of the crime of facilitating illegal immigration, and to the intersection of characteristics embodied by captains, an intersection that brings out the institutional racism of the prison system. Having been arrested on arrival, and not having any contacts or network in Italy, nor indeed any knowledge of Italian or familiarity with the prison system, are all factors that force people into a state of invisibility. Precisely in order to counter this process, and to protest against the use of pre-trial detention, three Palestinian detainees in Catania prison went on hunger strike.

We have also recently had contact with cases of abuse of solitary confinement, the overly-frequent use of which has a particularly deleterious effect on foreign prisoners. The people currently being put through extreme forms of such processes there include ‘M’., currently detained in a prison in southern Italy. After being diagnosed with HIV, M. was placed in solitary confinement "for health reasons," where he still remains at the time of writing. Over a prolonged period in solitary confinement, with little to no access to information about his illness, M. fell into a deep depression; over the last months he has committed periodic and serious acts of self-harm that have put his life at risk.

Working closely with his lawyer, we are looking for a suitable facility where M. can pass his sentence. Indeed, many of the prisoners who are in touch with us have asked for support in requesting access to alternative measures to detention. A number of lawyers have also made such requests to us, and occasionally even social workers in prison who have heard about our project. Although alternatives to detention are particularly difficult to obtain for people detained on charges of facilitating illegal immigration, we are currently contacting centers across southern Italy to map their availability to host people, while also monitoring legal strategies that might overcome obstacles to accessing these measures, and sharing our resources to facilitate the work of lawyers and in that hope of establishing jurisprudence in line with the Constitution, and which can create the possibility for captains to spend at least a part of their sentence outside of prison.

Data: An analysis of different strategies of criminalization by Italy and beyond

Through our daily monitoring of the news, we have counted the arrests of 75 people identified as migrant boat drivers since the beginning of the year. Egyptians continue to represent the nationality most frequently criminalized after arrival from the Libyan route; while we have noticed a relative increase in the number of people of Central Asia nationalities being placed under investigation after arrival from the Ionian route, i.e. of people departing from Turkey. One noteworthy difference compared to last year is the very low number of Turkish and Russian citizens arrested so far this year; we have not noted the arrest of any Ukrainians. Crucially, these 75 arrests amount to less than half of the number we recorded for the same period last year, in which we counted 178 such arrests. This decrease is even more remarkable if we consider that the number of arrivals to Italy has doubled this year, with around 60,000 people landing in Italy, compared to around 25,000 people for the same months of 2022.

Does this change mean that the criminalization of boat drivers might be coming to an end?

As much as we would like this to be the case, we don’t think so.. First of all, it is quite possible that the news of the arrests is not being reported with the same frequency as last year. Second, it’s important to note the correlation between the low number of arrests and the fact that most of the people arriving this year departed from Tunisia. This has been an important change: over the first half of 2022, about 5,000 people reached Italy through the Tunisian route, whereas this number has gone up to 30,000 people during the last 6 months. We recorded very few arrests following landings from Tunisia however. There could be a number of explanations for this, all connected to the dynamics of this route. For example, many of the boats crossing from Tunisia tend to be smaller and more self-organized than on other routes. More importantly, the Italian government continues to cut new deals with the Tunisian government, strengthening the deportation system between the two countries. Since a high number of arriving Tunisian citizens are criminalized for illegal re-entry to Italy, authorities perhaps find it more practical to detain Tunisians in hotspots or detention centers to facilitate a speedy deportation, rather than subjecting them to criminal trials as boat drivers.

Despite the sharply authoritarian character of Kais Saied’s government, including the institutional incitement to acts of racist violence and repression against black people, the EU has declared it will fund the Tunisian government to the tune of 100 million Euro as a contribution to its border management. In addition to this, a further 2 billion Euro has been promised by the IMF: policies of political blackmail justified, among other things, as “fighting people smugglers”. Saied’s government is not the only authoritarian government with which Italy is making agreements. The Italian government continues to donate ships to the Libyan military; just a few weeks after the Prime Minister, Giorgia Meloni, announced her intention to fight boat drivers “across the whole terraqueous globe”, the Libyan government sent out drones to bomb “smugglers” and their boats in civilian areas. Anything is possible, it seems, if it can be justified as a crackdown on smugglers.

The criminalization of boat drivers, migrant people and other facilitators of movement has been carried out in different ways over the last months, and not always through the use of criminal law. We have had a chance to see this by accompanying and closely supporting two Gambian captains who were released in mid-April after having completed their prison sentence. The consistent use of administrative detention means that both were immediately transferred to a deportation center upon release –one was released after a few days, while the other was detained for two months. Once they were both free, however, they had to face a harsh truth: the new law introduced by the Meloni government (the ‘Cutro Decree’) has eliminated the possibility for people to gain documents based on demonstrating their “integration” into Italian society, effectively meaning the elimination of the only possibility for them – and thousands of others – to have documents in Italy. The law and a “truly blind justice” are aligned against them.

Criminalization at sea – and on land

In its efforts to criminalize border crossing, Italy is closely collaborating not only with countries on the other side of the Mediterranean, but also with other EU member states. While the number of arrests following landings may have gone down, we have nevertheless noted an increasing number of people arrested in connection with more wide-reaching, transnational and expensive investigations and police operations, which also include Italy’s land borders. These operations have led to the arrest of more than 100 people in the first six months of the year alone.

A few examples. The investigation into ‘Hawala’ began in 2019 through a collaboration between the Italian authorities and Europol, and came to a conclusion two months ago with the arrest of nearly 30 people across Italy. Moreover, in April 2020, at the height of the pandemic, the police launched operation Astrolabia, establishing a collaboration between Albanian, Greek and Italian police forces to try and block arrivals in Puglia, leading to more than 20 arrests including that of eight Ukrainians suspected of boat driving. In the same year, the anti-Mafia directorate in Reggio Calabria followed a group of Afghan car drivers who were helping people from their community to arrive in European countries: operation Parepidemos led to the arrest of four Afghan citizens in France and Germany. Similarly, in 2022 the anti-Mafia directorate in Catania initiated another investigation, Landaya, which led to around twenty arrests throughout Italy of people from West Africa, in coordination with the French police. In a connected operation, Pantografo, the Italian authorities – again with their French counterparts – carried out the arrest of 13 people in the tent-city at Ventimiglia, in a blitz at dawn that was splashed across the newspapers, replete with police dogs and helicopters.

We can’t help but ask ourselves the extent to which these investigations might be a kin to those which led to the criminal trials against four Eritrean citizens who spent years defending themselves from accusations of facilitation that are very similar to the ones described above. Indeed, after being held responsible for exploiting other Eritreans both in the first trial and in the appeals court, they were finally found innocent in the High Court. Cases such as these demonstrate that acts of helping people across borders can often be better interpreted as acts of solidarity and self-organization of migrant communities. We spoke about this in more detail – along with Carlo Caprioglio and Karl Heyer – in an article published on the Border Criminologies blog.

Growing a network from the Mediterranean to the English Channel

April saw the conclusion of a series of trainings we designed primarily for lawyers to examine the criminalization of captains from a legal perspective. Beginning in September 2022, the aim of the series has been to develop a network of lawyers that can ensure a full and effective defense for captains on trial. The trainings took place in three cities across Sicily (Agrigento, Palermo and Catania), each with a specific legal focus. The first focused on the importance of defense investigations and the crucial role of defense witnesses; the second focused on different applications of the crime of facilitation of irregular immigration, and possible defense strategies in the light of ECHR regulations; the third focused on legal support during detention, with particular reference to access – and obstacles in accessing – alternative measures to detention. Our thanks to the lawyers from Borderline Sicilia for taking the lead in organizing the trainings, the bar associations in Agrigento, Catania and Palermo, the forensic association Fucina Legale of Catania. Finally, and also Radio Radicale for recording the meetings.

We spoke about the criminalization of captains and facilitators in the Mediterranean with Radio Blackout in Turin; but it’s important to underscore that criminalization doesn’t take place only in the Mediterranean, but also in many other places, including the English Channel. For the past year a new British law has intensified criminalization, meaning that increasingly more people are arrested on arrival in the UK. In June we participated in a public meeting alongside Captain Support UK - the local group of the transnational Captain Support network, of which we are also part. Here we introduced the topic and our project to groups engaged in different struggles in London (including LGSM, and the Anti-Raids network) and to discuss our work and prospects from a more transnational perspective. Just as we do, the British group monitors arrests, trial hearings and release from prison of criminalized persons; however, they also manage to maintain contact with detainees through prison interviews and phone calls – a means of communication we have found to be very difficult to access in Italy for people who are not direct relatives. Our thanks to everyone who participated, as well as May Day Rooms for hosting us.